When Scott Crowder played his final game for the Massachusetts Minutemen — a heartbreaking overtime loss in the third game of a best-of-three Hockey East quarterfinals series against Northeastern in 2009 — he knew one thing: He didn’t want his life in hockey to end.

A professional playing career wasn’t too likely for this four-year role player. He could ride buses in one of the low-tier minor leagues, but with two degrees from UMass — one in sports management and the other in business — that seemed like the waste of a great education.

Still, anyone familiar with the sports world knows that you can’t just walk into a sports job.

Crowder, though, had an entrepreneurial spirit. That, combined with his education, gave him a step up on many who needed to rely more on working for a sports team or organization for that magic job in sports.

Using his passion, Crowder instead decided to create his own job in sports.

Taking to the pond

For years his family, which includes his father Bruce, who played four seasons in the NHL and coached Division I college hockey for 17 seasons, his mother Lucie and older brother Kevin spent their summers on Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire. Scott knew the small town of Meredith, N.H., like the back of his hand.

While a destination for vacationers in the summer, Meredith virtually shuts down in the winter. Those with cabins and houses in the area, though, know that Meredith’s lakes are perfect for one thing in the winter time: pond hockey.

Crowder suddenly had his sports career developed: He would host one of the largest pond hockey tournaments in the nation in Meredith, N.H.

Months after graduating, Crowder began the planning for the inaugural event and called one of his professors from UMass for advice. Crowder was planning on hosting the event just a short three months later and his professor had sound advice: wait.

Crowder, though, went ahead and began the planning. At first, he wasn’t welcomed into town. He received little support from the surrounding businesses and had to go through much of the leg work in planning on his own.

What became the New England Pond Hockey Classic was an immediate success in year one. The field was fully subscribed with more than 70 teams from all around the country.

After year one, the local community began to take notice.

“At first, the community didn’t have a clue who I was,” said Crowder. “Now pretty much everyone in the town knows who I am.”

About to enter its third year this Feb. 3-5, the New England Pond Hockey Classic weekend in little Meredith, N.H., now represents the town’s biggest financial weekend of the year, this for a town that for decades has been nothing but a summer vacation destination.

“The main restaurant in town would usually shut down at 8 p.m.,” said Crowder. “That weekend, it’s the place to go. They stay open right until last call [at 1 a.m.].”

The 2012 edition of the tournament has long been sold out. Two-hundred teams will take the ice this year and there is a massive waiting list in case anyone backs out.

The success of a for-profit event, though, wasn’t enough to satisfy Crowder.

Recycling for the future

Crowder remembered his hockey roots. Coming from a hockey family, he was on skates at an early age. Having a father who played professionally and coached, there were always plenty of skates, sticks and pads around the house.

But Crowder remembered that wasn’t the case for all his friends. Growing up in Nashua, N.H., he was hardly from a poor community. Still, not every friend’s family had the money to shell out for their kids to play hockey, easily the most expensive of the four major North American sports.

Knowing that could happen in an upper-middle-class town, Crowder knew that there were plenty of communities where kids who idolized hockey players couldn’t play the game themselves.

Crowder sought a way to help but the small financial contributions he personally could make — less than two years out of college and making just modest profits off his pond hockey tournament — wouldn’t go very far.

Then he remembered all of those piles of used hockey equipment that sat in his basement as a kid. Crowder thought if he could find a way to collect used equipment, particularly in the ever-evolving technology and equipment in hockey, he might be able to find a way to outfit kids whose families would never be able to afford equipment, thus giving them the chance to experience the game.

Crowder’s idea was hardly unique. Used sports equipment has sold in stores like Play It Again Sports for years. Rarely, though, is that used equipment given away.

Still, not seeking to recreate the wheel, Crowder began an Internet search that led him to Michael Spengler, a former college hockey player himself who spent four seasons at Bentley. Spengler was attempting to establish Restore Sports, a company that would collect used equipment from all sports to provide back to children in need.

When Crowder contacted Spengler, Restore Sports was still in its infantile stages. Together, the two decided to focus their efforts first on the sport they knew best: hockey.

So was born Restore Hockey. The organization began small, using the networks that both Crowder and Spengler had to begin setting up donation spots where they could collect equipment.

That small network, though, was stronger than many would think. Organizations like the Boston Bruins and Hockey East embraced Restore Hockey’s mission.

Last year, in Restore Hockey’s first year of official operation, the non-profit held donation events at Bruins games as well as events at each of the 11 Hockey East schools.

What originally was about equipment, though, quickly morphed. Restore Hockey teamed with Pure Hockey, a New England-based equipment supplier, to negotiate the purchase of “starter packages” — skates, pads, a stick and basic uniform — that would be enough for any beginning player to get his or her first crack at the ice. At a price point of $150, Crowder and Spengler could solicit financial contributions from individuals and organizations to purchase these starter sets.

Hockey’s biggest stage

In just one year, the credibility of Restore Hockey built. Timing was also very much on Restore Hockey’s side.

The NHL recently announced its “NHL Green” initiative, an effort to reduce the overall environmental impact of the league. Restore Hockey became one of the cornerstones of the league’s initiative.

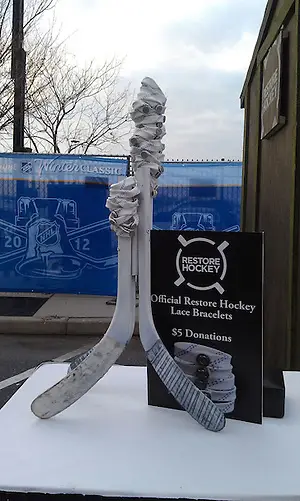

That led to Crowder and Spengler being invited to the recent NHL Winter Classic at Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia. Restore Hockey was given booth space at Spectator Plaza throughout the entire festivities associated with the NHL’s highest-profile in-season event.

Restore Hockey collected both used equipment and financial contributions throughout the three-day event.

“It was an awesome experience,” Crowder said of the weekend. “To be a small non-profit on that big of a stage was incredible. What we wanted to do was not embarrass ourselves out there and we did the exact opposite. The awareness we got and the support we had from the NHL and the greater Philadelphia community was great.”

Restore Hockey collected 100 pieces of equipment that will be donated to the Ed Snider Foundation, which helps teach children life lessons using, among other things, hockey to bring together a diverse population.

For the event, Crowder and his team developed Restore Hockey bracelets to sell at the event. The rope bracelets that resemble a hockey skate lace were sold for $5. Anyone who bought a bracelet was entered in a drawing for signed memorabilia from the likes of Jaromir Jagr, James van Riemsdyk and Patrick Kane.

Selling the bracelets alone raised enough to purchase 10 new starter equipment packages.

The Winter Classic also exposed Crowder and Spengler to the game’s top influencers, from agents to corporate sponsors as well as NHL owners and executives.

Crowder hopes that the Winter Classic, along with Restore Hockey’s ongoing efforts to grow the organization’s impact, will be a springboard to a positive future.

“The Winter Classic shows that a small non-profit can have an impact in the sport, even on as big a stage as that,” said Crowder. “There were a bunch of people coming up saying, ‘I could outfit a whole hockey team with the equipment I have in my basement.’ It’s nice that these people now know there’s a place they can donate their slightly-worn equipment and not have it end up in a landfill or in the basement.”