Part II: Youth Hockey

By the time Ryan was eight years old, he was playing for two teams. The two could not have been more different.

He had begun with Pentucket Youth Hockey’s Learn-To-Skate program. When he turned six, he graduated to Mite Instructional hockey, where coaches skate on the ice to provide direction and a buzzer signals the line shifts, even if there’s a breakaway. In Ryan’s season of Mite Instructional hockey, he scored a single goal.

Within two years, however, his hard work at developing his skills had moved him up to Pentucket’s top Mite team. And what a team that was. It would go 21-5-2 and win its league’s championship game, a nailbiter in which Ryan’s picturesque breakaway goal was the decisive blow. After the game, the head coach called it “our biggest goal of the year.”

At the other end of the spectrum, however, was Ryan’s other team. It would play over 30 games and win only once.

The Lowell Jr. Chiefs played within the high-octane Metro Boston Hockey League. “Metro” hockey, as it was called, offered the best competition, the best coaching and the most extensive practices. Although it was far more expensive and demanded a gargantuan increase in travel over playing “town” hockey — games might be more than two hours away — the rewards seemed well worth it. Metro’s track record of developing the best players was hard to argue with.

For all Metro’s selling points, however, parity wasn’t one of them. Town teams could take players only from their allotted region and played parity rounds early in the season to allow them to move up or down to an appropriate division within their league so that all teams were competitive.

Not so within Metro. All the kids who were born in 1984, Ryan’s birth year, played in the same division. If your team wasn’t competitive, too bad; you might want to switch to a better one next year. Unlike town hockey, you could try out wherever you liked, a fact that resulted in many of the best players congregating on the same teams. After all, it’s a lot more fun to win all the time than get the snot kicked out of you. Powerhouse programs such as the Jr. Terriers and the South Shore Kings, for example, featured Kenny Roche, Ray Ortiz, Sean Sullivan and Brian Boyle, already dominant stars at this level.

The Jr. Chiefs, on the other hand, were a ragtag group with only a few diamonds in the rough like Ryan and quite a few more lumps of coal, kids who weren’t going to shine at the elite level of Metro hockey no matter how much they might be buffed and polished.

This Jr. Chiefs team, however, had one major selling point. Its coach, Dave Brien, held the equivalent of a USA Hockey Master level certification. He’d attended week-long coaching symposia as far away as Calgary, Alberta, places where he’d talked shop with coaches from the NHL and various national teams, men who made their living at coaching. To think that anyone else could teach Ryan more about the game was folly.

“We’ll get our brains beaten in for a while,” Brien admitted. “But we’ll try to hold onto most of our good kids, and eventually we’ll be very good.”

It turned out to be an accurate prediction, but that still didn’t make it easy to take the seemingly endless string of lopsided losses. The key was keeping your eye on the prize. My philosophy was that when it came time to impress high school or college coaches, no one was going to ask Ryan what his won-loss record was as an eight-year-old. They were only going to care how good a player and teammate he was. In that respect, Ryan was making leaps and bounds.

“He grew from a timid, somewhat shy kid to a leader who was a dominant aggressor,” Brien says. “He was extremely coachable. He took everything as gospel and really grew over the years.”

And so when championship-caliber Metro teams came calling, even those much closer to home, we stayed with Dave Brien. Driving an extra half hour each way to practices was a more than reasonable price for exceptional coaching, a philosophy that extended to my daughter Nicole’s competitive swimming as well. One year that she trained with a particularly distant swim team our two cars’ total mileage exceeded 100,000 miles. Small wonder that we were never driving the last models, but instead running a string of jalopies into the ground.

Of course, had the Jr. Chiefs gone 1-30-1 year after year, Ryan might have become too accustomed to losing and eventually lost his competitive fire. That never happened, however. During the Chiefs’ toughest years, Ryan’s Pentucket teams were either winning championships or were in the hunt. By the time we parted ways with Pentucket Youth Hockey, the Chiefs had become quite competitive.

Only one of the many early losses with the Jr. Chiefs still rankles. We were facing one of the most highly skilled teams in the league and clearly could not compete if we allowed the game to be a one-on-one skills competition. Metro, however, was a full-check league at all age levels, so Dave Brien decided that we had to slow them down by being physical. Not dirty. Not goons. But we had to finish our checks. We had to emphasize taking the body. Otherwise they’d be dangling with the puck for three periods and putting many of them in the net.

Even so, the end of the game neared and we still were losing, 7-0. It had been the correct strategy to employ, but the skill disadvantage was just too great.

In the final minute, however, I was stunned to see the other team’s goalie skate to the bench as his teammates entered the offensive zone. I looked at the officials, but there were no delayed penalties signaled.

In a game played by nine-year-olds, the coach of a team leading 7-0 had pulled his goalie to try to add an additional goal.

In the post-game handshake, I came to the coach — who shall remain nameless, but has an unmistakably feminine voice and a name at the end of the alphabet — and said, “You pulled the goalie with a 7-0 lead?”

The coach averted his eyes and said, “I didn’t like the way your team played.”

We had played clean, getting only one penalty for a hit that had been excessive, but that fact didn’t matter to this guy. He had pulled his goalie with a 7-0 lead.

When years later his son, who had been a big-time star as a nine-year-old, failed to make it in Division III, the phrase “the sins of the fathers” came quickly to mind.

If that had been coaching behavior at its worst, I also saw parental behavior at its worst… and almost became a victim of it.

While still coaching Ryan’s town team, I corrected a player’s mistake after he came to the bench. I did so in an even tone and at low volume — as low key as you could get. After all, these were only 10-year olds. And even though the mistake was a point we’d been emphasizing, I was making the correction in as gentle a way possible.

“Go (bleep) yourself,” the kid said.

Hello?

I hadn’t gotten in the kid’s face. I hadn’t screamed and hollered. I had merely corrected a mistake. If youth hockey coaches aren’t correcting mistakes, they aren’t doing their job. And I had been told by a 10-year old to go bleep myself.

I motioned to the back row. “Sit back there,” I told him. It was the third period and he would sit there for the rest of the game. This wasn’t the first time the kid had been a disciplinary problem, but this had taken the issue to another level.

Afterward, the father confronted me. He was a mountain of a man without being six feet tall. At the time I was in pretty decent shape myself, but this guy had a bodybuilder’s muscle-bound physique. If we arm-wrestled, he might have snapped my forearm like a twig.

I explained the unacceptable behavior and the father responded that his son had Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD).

“That’s not ADD,” I said, mindful of the kid’s escalating disciplinary problems. “That’s bad behavior. And you aren’t doing your son any favors by blaming it on ADD.”

The guy went nuclear.

He pulled off his leather biker’s jacket and yelled, “I was in prison for three years! I ate guys like you for breakfast!”

Fathers of other players quickly moved in between us and pulled me into another room.

As they did so, I said, “I’m not afraid of him.”

It was a line of such absurdly misplaced machismo that it became comic fodder for one parent. If someone made a comment of monumental stupidity, that parent might nod and whisper to me, “I’m not afraid of him,” and we’d laugh.

It was funny until years later an enraged hockey parent, Thomas Junta, beat Michael Costin to death over an on-ice dispute.

After that, “I’m not afraid of him” didn’t seem funny at all.

Every decision that we made was a decision that we made. I didn’t dictate anything to Ryan. Our relationship was 99 percent best buddies and only one percent with me as a parental authority figure. It was an approach that would work only with an exceptionally mature kid, but Ryan was every bit that, as was his sister. I’d like to think that was because my wife and I did a lot of things right, but we were also very lucky.

We’d sit down and discuss the alternatives and figure out what was best. This held true for small decisions — “North Andover’s power skating is tonight, wanna go?” — or big ones like leaving Pentucket Youth Hockey.

Leaving Pentucket Youth Hockey was surprisingly easy. Far easier than I would have expected years earlier and far easier than it should have been.

In what would have been Ryan’s final year as a Mite, USA Hockey instituted a six-month age change that would have kept him from moving on to Squirts. Since this would have been a developmental disaster, I petitioned the Pentucket board that he be allowed to “play up” as a Squirt.

The board granted that request on the condition that he be picked for the Squirt 1 team during tryouts. If not, he would remain a Mite.

That was a hurdle easily cleared. Outside evaluators brought in to perform unbiased assessments rated him as the fifth best Squirt out of somewhere between 40 and 50 kids, underscoring how pointless it would have been to remain a Mite. If you’re one of the top five players in the nine-and-10 year old category, you don’t belong playing against seven- and eight-year olds.

Politics, however, soon reared its ugly head. The composition of the board changed, as it did every year, and the new board ruled, without bringing in any of the affected parties to state their case, that this had been a one-time exception. When it came time for Ryan similarly to play up as a Pee Wee, he would instead be forced to play a third year as a Squirt.

I considered this backstabbing at its worst since I had served each year as a coach and also as the editor of the organization’s newsletter, yet I hadn’t even been given the courtesy of stating my case to the board. Sadly, jealousy often reigns supreme among those whose kids haven’t developed the skills to make the top team.

When we were eventually faced with that scenario of Ryan playing a third year as a Squirt, we concluded it was time to leave town hockey for good. An escalating number of conflicts between the two teams’ schedules — initially trivial, but increasingly frequent — made the decision only a matter of time, but the way it was done still left a sour taste in my mouth.

The Jr. Chiefs played and practiced at the Tully Forum, the same place where the Massachusetts-Lowell Chiefs — soon to be renamed the River Hawks — competed. Ryan and numerous teammates attended many games there, watching the likes of Dwayne Roloson, Christian Sbrocca and Greg Bullock. Ryan also attended many Hockey East tournaments, NCAA Regionals and Frozen Fours.

One Frozen Four, in particular, stands out. He was probably nine years old or so and was the only non-adult at a HOCKEY-L gathering between semifinal games, HOCKEY-L being a college hockey email distribution list that predated USCHO.

There was the usual socializing and many had dubbed me HOCKEY-L Dad of the Year for allowing Ryan to miss school so he could attend the Frozen Four. Missing school wasn’t something I took lightly, but it happened once a year and Ryan was an excellent student so there seemed no harm in it.

What became memorable, however, happened near the end of HOCKEY-L’s allotted time in the room. The organization that had rented the next time slot had hired the Hanson brothers of Slap Shot fame to make an appearance. They arrived early, decked out in Charlestown Chiefs jerseys, and began mixing in with HOCKEY-L people.

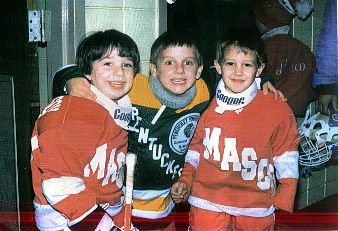

One of the Hanson brothers immediately spotted Ryan, knee high to the proverbial grasshopper, decked out in his Jr. Chiefs hockey jersey and wearing a baseball-style cap.

“Hey, kid, what’s your name?” asked the Hanson brother.

Ryan answered.

“I like your hat,” said the Hanson brother.

“Thanks,” Ryan said.

“I like your hat a lot,” the Hanson brother said, taking it off Ryan’s head and putting it on his own, flashing “the foil” in the process.

Ryan grinned from ear to ear.

“I like that jersey, too.” The Hanson brother began to pull it over Ryan’s head in the manner the self-styled goons would have attempted during a fight.

It was a hilarious sight that had everyone laughing.

Eventually, the clowning around was over and Ryan got his hat back. He also had a rare treasure … a story he could recount to his hockey buddies about the time he’d tangled with one of the Hanson brothers and lived to tell about it.

Part III of this series covers summer hockey.