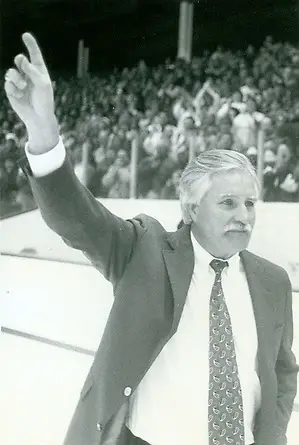

Ron Mason has not coached a college hockey game in over 10 years. He is back in the spotlight this week as he and his successor at Bowling Green, Jerry York, stand tied with 924 wins, tops in men’s college ice hockey. York’s Boston College Eagles beat rival Boston University last Saturday to pull himself even with the standard bearer of success in college hockey.

York will break the record in the near future, maybe as early as Friday at Providence. Mason will call to congratulate him and probably start the conversation with this type of tongue-in-cheek remark: “You know, you can thank me for some of those wins. I left you a great team at Bowling Green.”

York and Mason have an extensive history with each other, starting with when York followed Mason at BG. They clashed a ton of times in the 1980s when Bowling Green and Mason’s Michigan State were two of the heavyweights in the CCHA. They are each part of the legacy of the CCHA, which is in its final season.

[See also: Ron Mason’s coaching history :: Coaching wins leaders]

Mason has been the classy elder statesman in the past couple of weeks as he has done the interview circuit talking about his accomplishments and the legacy he left behind. Mason passed BC’s Len Ceglarski to become the winningest coach in college hockey and the record comes full circle as another BC coach will pass him for No. 1. Through it all, Mason seems to be enjoying talking about it because it allows him to talk about what matters to him a lot: college hockey.

Mason never thought he’d be a college hockey coach despite playing for two men who have had a tremendous impact on the game. The first was Scotty Bowman (who happens to be the NHL’s winningest coach) in the Peterborough Petes organization and Sam Pollack, the legendary multi-Stanley Cup-winning former general manager of the Montreal Canadiens whose system of doing things right is still utilized by all of the NHL execs that went through either the Canadiens or Montreal Junior Canadiens system.

“Sam taught you early on as a player and that was play hard and play with heart,” Mason said last week from his home in Florida. “He always told us [to] do things right and told us why we did what we did. It worked, and I never forgot it.”

It was in his early years that Mason’s philosophy developed as a coach, although he hardly knew it at the time.

“My Pee Wee coach, and I just can’t remember his name, was the first guy who taught me as a center where to go and where to be in relation to where the puck was,” Mason said. “He taught me a system and how to play it. It was a great system. I took it to Lake [Superior State], BG and Michigan State and it worked in all three places.”

Mason laughed when he repeated a story to me that he has told me many times. His coaching career, much like Jack Parker’s at BU, started somewhat on a whim. Parker was selling insurance and decided that the one thing he knew better than anything was hockey. That started his path back to BU and becoming the legend he now is.

Mason was also a student of the game with the passion for teaching it. He was doing work toward his masters degree at Pitt after a terrific playing career at St. Lawrence, leading the Saints to their first national championship game appearance in 1962-63. Then, one day, it hit him.

“I hate to say this, it sounds bad, but I just got sick of school after finishing my masters and decided maybe I could become a hockey coach,” he said, sounding as he was reliving the moment his life took that momentous turn.

Mason applied at Lake Superior State and then Division II Merrimack. (Here is a twist of fate: Merrimack almost had Mason as a coach and actually had 1980 Olympic hero Mike Eruzione committed to school before BU convinced him to go play Division I).

“I got both jobs and in those days you had to teach and coach. I had my degrees so that wasn’t a problem for me. I chose Lake because I wanted to start my own program.”

The rest is history for Mason, who has created a legacy in college hockey. The coaching tree of assistants who came through his tutelage includes two-time national championship coach George Gwozdecky of Denver and two-time national championship coach Rick Comley (now scouting for Chicago and fifth on the all-time wins list). The late Shawn Walsh, Mason’s former son-in-law who won two titles at Maine and longtime professional coach Newell Brown, currently an assistant with the Vancouver Canucks, also spent time with him in East Lansing.

“Jeff Jackson was on my staff for a few days at MSU, then he got the Lake State job,” he joked as he thought of those now coaching who came through his programs.

The list goes on and on:

USA Hockey National Team Development Program coach Danton Cole; former Alabama-Huntsville coach Chris Luongo; former Harvard coach Mark Mazzoleni; Frozen Four runner-up Bob Daniels of Ferris State; longtime UAH coach (now retired) Doug Ross; former BG player Ted Sator, who had a good career in the NHL as a head coach; former Ohio State coach John Markell; the legendary Steve Cady of Miami (who got a rink named after him for his accomplishments); and current MSU coaches Tom Anastos, Kelly Miller and Tom Newton.

Newton is the only person to have been an assistant to both Mason and York and has seen many of the combined 1,848 wins by both men. Caps GM George McPhee and longtime NHL player and now scout Brian MacLellan also played for both Mason and York, as did Newton.

Mason retired at a time when he was physically and mentally sound and could have gone on. People used to ask him why he didn’t want to continue and try to win 1,000 games. For him, it was pretty simple on two levels.

“As a coach, you worry about the next game, not 900 wins or 1,000 wins,” Mason said. “You play to win the next one and hopefully those include a national title or two. Winning is great, having a good program is great, but it takes a lot to sustain it.

“The other thing was the opportunity to become the [athletic director] at MSU and that was a challenge I was looking forward to. I’m glad I retired when I did.”

Nine hundred and twenty-four wins, according to Mason, was a combination of a lot of things. Like York, who has echoed these sentiments at every milestone win in his career, Mason used words like perseverance, dedication, work ethic, respect, good players and great assistants.

“So many things outside of you go into winning that much,” he said. “I was really lucky to have a lot of things that helped me be successful. Maybe most important was being at schools that gave us an opportunity to win.”

Mason sits back now and watches his grandsons carry on the tradition. Grandson Travis Walsh is a freshman defenseman at MSU. Travis’ brother Tyler, who last summer survived a potential life-threatening illness, is the video coordinator at Maine. Both are sons of the late Shawn Walsh and the pride and joy of “Papa” Ron.

“The kids lost their dad when they were young and it was important and rewarding to be a big part of their lives and my wife and I have really enjoyed that,” Mason said on one of the benefits of retiring when he did. “It is great to see them have hockey, have that as a big part of their lives. They both love it.”

For Mason, they are each in a place that has a connection to the Mason-Walsh family: East Lansing and Orono.

Tyler is a spitting image of his dad. Mason made a guest appearance by phone on the CBS Sports Network broadcast of Vermont-Maine last Friday to talk about the record. Host Shireen Saski surprised Mason by bringing Tyler in to ask the last question of the interview. What he said could have been the words of his countless coaching proteges, All-Americans, national champions, NHL players, Hobey Baker Award winners and finalists and those who benefited from being part of a Ron Mason-coached team.

Said Tyler: “Thank you for being a role model, for all of the support you have given me and for being someone I could look up to.”

Mason soon will look up to someone after years of holding that top spot on the wins list. It will be at his friend Jerry York, who will slide one notch above him on a list headed by two of the game’s greatest coaches and people.