When one thinks of big-time college hockey, 1998 was the Year of the Arena.

Four different schools opened new, highly-touted buildings, all significantly increasing their capacity. Two were monstrosities – Wisconsin opened the Kohl Center seating 15,237 for hockey and Ohio State christened the Shottenstein Center, even larger with as many as 18,809 seats available.

Both were and continue to be multi-sport arenas, hosting both hockey and basketball, and both were significant upgrades to the predecessors – Wisconsin moving from the 8,600-seat Dane County Coliseum and Ohio State making a massive upgrade from a 1,400-seat OSU Ice Rink.

In Colorado Springs, Colorado College was settling into the new Broadmoor World Arena, an 8,100-seat facility upgrade from its predecessor, which sat about 3,000. And UMass Lowell, which for years played at the Tully Forum about eight miles off campus, more than doubled its capacity when it moved to the Tsongas Center, which currently seats a little more than 6,000.

Those who love big arenas were in their heyday. Even those venues were topped when North Dakota opened what many considered a palace, Ralph Engelstad Arena, three years later. The 11,640-seat venue has been at, near (and sometimes probably above) capacity nearly every North Dakota men’s hockey game since.

Sadly, though, “the Ralph,” as it is affectionately known, is pretty much the only one of this group of large arenas that in recent years has posted anywhere near capacity. Add to that lists buildings like 3M Arena at Mariucci, home of Minnesota; Agganis Arena at Boston University; and the Mullins Center in Amherst, Mass.

Sure, there are nights when these buildings approach or reach capacity. But on the average night, even reaching two-thirds of capacity can be a struggle.

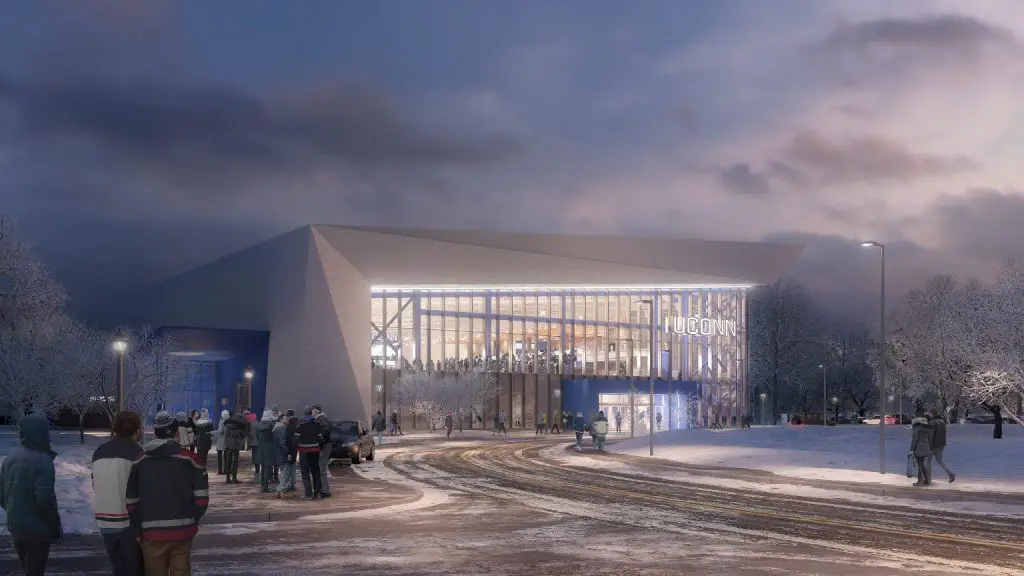

Thus, we’re seeing a new building trend, one that was on display last Saturday morning when Connecticut broke ground on its first high-end on-campus arena, the final building block in an impressive athletics campus that athletic director David Benedict refers to as UConn’s “Olympic Village.”

Similar to the buildings of the late ’90s, UConn’s facility will come with a high price tag, reportedly $70 million if things stay on budget.

But unlike its 20th century counterparts, UConn won’t sport a massive capacity.

Instead, this arena will feature a little more than 2,600 seats with a standing-room capacity that will push 3,000. That doesn’t mean that this won’t be an attractive venue for future Huskies.

A focus on amenities

Like a fine resort, UConn isn’t focused on volume as much as it is the experience. Despite a smaller capacity than the average arena in Hockey East, no coach would be ashamed to show this building to recruits. Locker rooms will feature high-end elements with sport-specific training facilities just yards away from the locker rooms, a training room with hot and cold tubs and an area specifically dedicated to players working on shooting.

Fans will also be treated to the best, including a club area that men’s hockey coach Mike Cavanaugh thought was important after seeing Notre Dame’s Compton Family Ice Arena in South Bend.

“I thought it was important – and I saw this at Notre Dame – they have a super club room and I wanted to make sure we have one of those,” Cavanugh said. “We were able to put one of those in and it will double as a place for a pregame meal and any type of banquet [space] we might [need].”

Fitting in by being different

In June 2012, the UConn men’s team announced that it would transition its membership into Hockey East beginning in 2014. The university’s women’s team was already a Hockey East member.

At the time, there was a commitment by the school to build an on-campus facility while beginning play at the XL Center, the former home of the NHL’s Hartford Whalers. Needless to say, things didn’t exactly move swiftly. Despite promises of state funding, final commitment didn’t come until just months ago, though administrators last Saturday often referred to the multitudes of meetings and planning that has occurred during that time.

“The league and member schools showed a lot of patience,” said Benedict. “Something things take longer than you expect, but I assure you the wait will be worth it.”

When UConn entered the league, the commitment was for a 4,000-seat facility. When it was announced the final count would be closer to 2,600, criticism across the board was swift, though when one sees the final plans, that’s likely unjustified.

The 4,000-seat capacity number was established in years past when the league was looking for new membership. The reality, though, is even that number might not be an overreach.

Taking the attendance from the 2019-20 season in Hockey East, the average attendance at all games in Hockey East buildings was 3,650. Now if you’re not familiar with college athletics and reporting of attendance, particularly at the more popular sports, schools typically inflate attendance numbers, sometimes heavily.

At an average of 3,650, that’s still an average of just 66.45% of total capacity.

And one thing that was left out was postseason attendances as, you may recall, the 2020 postseason was canceled due to COVID.

One thing some don’t know about the postseason is that schools are incredibly honest in reporting attendance for postseason home games. The reason? Well, the league is given the ticket sales proceeds in the postseason, thus every person you report in the building translates to a dollar figure you must pay the league.

(For a matter of comparison, the 2018-19 season that included on-campus playoffs in the quarterfinal round had a season-long average attendance of 3,326).

So, for the sake of argument, let’s say that on average a school may mark up attendance by 20%. If your league average is 3,650, mark that down to 3,041 to account for that attendance “fluff.”

That 4,000-seat minimum doesn’t necessarily make sense.

UConn still will have the option to play games in downtown Hartford at its current home, the XL Center, but according to the UConn AD, that’s not necessary in many cases.

“That number that was a requirement is no longer a requirement,” said Benedict. “We’ll be able to play here whenever we want to play here.

“We talked to a lot of our peers in Hockey East and in this region. The people that I spoke with, the athletic directors at all these programs, I think we’ve picked a size arena that is going to be appropriate for our area and our program.

“It’s going to allow us to sell it out whenever we play in it. I’d rather play in an arena that is sold out every game than play in a facility that is half empty all the time. It’s going to be a loud facility.”

A benefit to the women’s side

UConn women’s coach Chris Mackenzie, whose team lost to national runner-up Northeastern in the most recent Hockey East title game, joins those excited by the UConn arena.

Prior to the 2020-21 season, when COVID forced both the men’s and women’s teams in Freitas Ice Forum, the current on-campus facility that resembles more of a high-end youth hockey arena rather than a proper Division I building, Mackenzie’s women’s team was the only team skating on campus.

He has no problem sharing the new space when the arena opens, particularly given the size, something he sees fitting of most any women’s program in the nation.

“When you look at attendance, historically we’re going to have a smaller crowd than the men’s [team],” said Mackenzie. “This arena is an ideal size for any women’s team. We’re really happy with that.

“If we can get our regular crowd of 300 to 500, it’s going to feel like there are people in the building. It’s going to be a great venue for a student-athlete.”

Setting, or maybe following, a trend

When you look at the most recent arenas that have been opened across college hockey, smaller seems like the future.

The largest of the recent arenas are Notre Dame’s Compton Family Ice Arena and Penn State’s Pegula Ice Arena. Sure, each has a capacity north of 5,000 with Pegula able to seat a little more than 6,000, but in comparison to the rest of the Big Ten – particularly Minnesota, Wisconsin and Ohio State – these buildings are smaller.

But in other leagues you have Quinnipiac, which plays at the People’s United Center, a 3,386-seat building known for generating one of the better atmospheres in college hockey.

Colgate recently opened the Class of 1965 Arena, capacity 2,222. Bentley Arena at Bentley University boasts a capacity around 2,000.

And then we can circle back to one of the schools that called home of the great 1998 arenas: Colorado College.

While the 8,000-plus-seat facility has been a great home, the school decided almost two years ago to build a smaller on-campus facility, Robson Arena, which will seat just 3,407. The odds of that facility being near or at capacity in the future is much better than at the Broadmoor World Arena.

But in a day and age where competing for every entertainment dollar is becoming increasingly more difficult, it’s likely when it comes to arenas that smaller may be better.